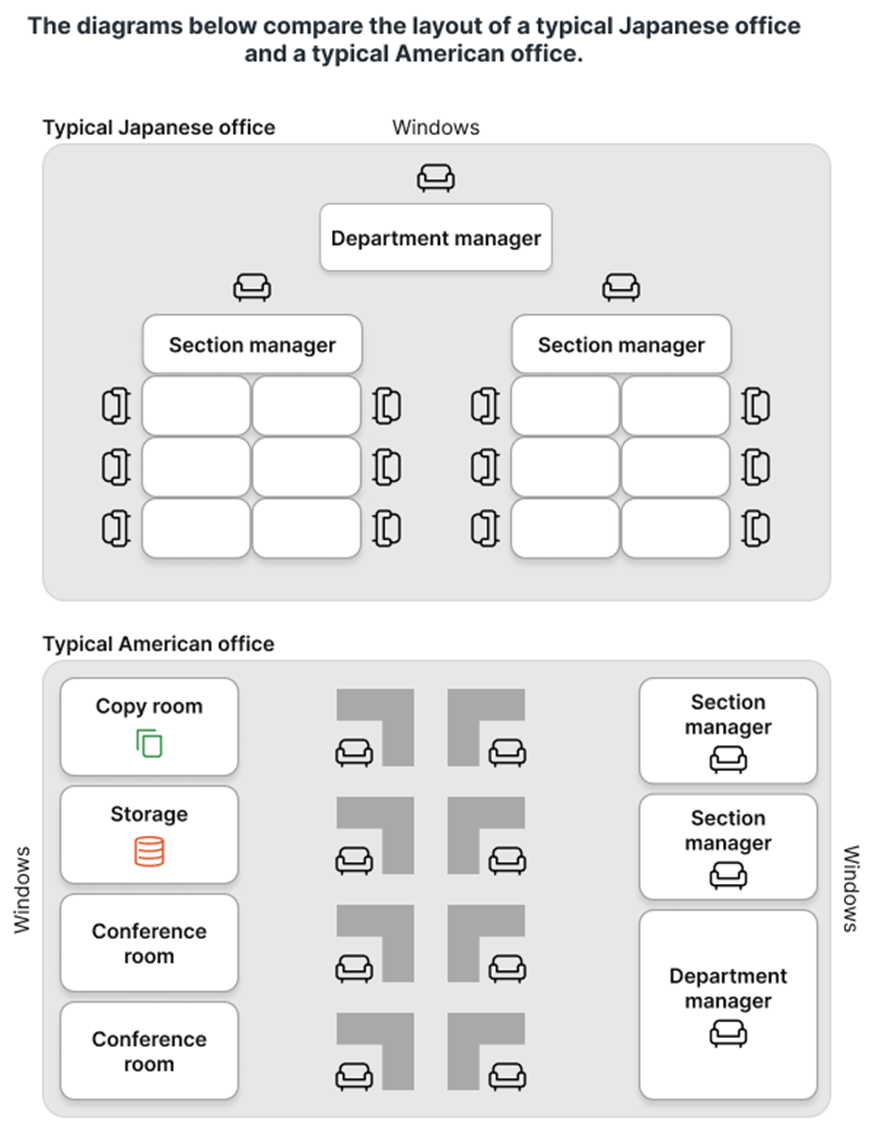

The diagrams below compare the layout of a typical Japanese office and a typical American office.

Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant. Write at least 150 words.

The diagrams below compare the layout of a typical Japanese office and a typical American office.

Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant. Write at least 150 words.

Câu hỏi trong đề: 2000 câu trắc nghiệm tổng hợp Tiếng Anh 2025 có đáp án !!

Quảng cáo

Trả lời:

Sample 1:

The pictures compare the layout of a typical office in Japan and America.

Overall, the office setups in Japan and America are diametrically different, with the former encouraging collaboration at the workplace and the latter reflecting the independent working style.

In Japan, tables of members in the same team are placed together to facilitate group discussions, forming two large areas, each of which is overseen by a section manager. Meanwhile, the space of an American office is divided into separate cubicles with high walls to minimize distractions. The working station of the Japanese department manager directly faces the joint desks of his subordinates, offering him an overall view to monitor all the activities in the office. By contrast, the working spaces of the management team including two section managers and one department manager are located separately with partitions on the East side of the American office.

There is only one window at the back of the department manager's seat in the Japanese layout whereas two windows are set up to stretch across the Western and the Eastern walls in the American office. While the office in America is equipped with a printer copier, a storage and two conference rooms, there are no such facilities in the Japanese office.

Sample 2:

The diagrams provide an insight into the layouts of a typical American and Japanese office, highlighting the main features and the functional areas of each.

The foremost contrast between the two office setups is the arrangement of desks and the presence or absence of certain facilities. While the American office demonstrates individualized workspaces and various amenities, the Japanese model features communal workspace divisions under the direct supervision of management. In terms of workspace arrangement, the Japanese model groups desks into two larger areas, each overseen by a section manager. In contrast, the American office designates individual cubicles for each employee, suggesting a distinct preference for personal workspaces. Interestingly, while the Japanese office has one window situated at the back of the department manager's seat, the American counterpart is equipped with two windows on the left and right walls, possibly indicative of differing considerations for natural lighting.

Regarding the provision of facilities, the Japanese layout is notably minimalistic, featuring no additional amenities beyond a solitary chair placed in the far corner. In stark contrast, the American office houses a printer, copier, and storage space on the left side, with conference rooms also available for use. Additionally, the section managers and the department manager are situated on the right side of the American office.

Sample 3:

The illustrations compare the configurations of a typical office in Japan and America. Generally, Japanese offices are designed to facilitate discussions among employees and supervision of managers, while offices in America emphasize individual privacy and hierarchy.

Regarding the arrangement of seating, in Japan, personnel are organized by sections. The employees are positioned parallel to each other around a rectangular table, which allows effective communication and exchange of ideas. The section manager is seated between the two lines so that he or she can supervise the work of their team members, while the department manager occupies the central seat to oversee the entire office’s operations. In comparison, offices in America are compartmentalized into distinct functional areas. In the middle are several separated L-shaped tables, each of which serves as the working space for an employee. Managers are arranged in adjoining rooms on one side of the office, highlighting the hierarchical framework of the institution.

Turning to other features, Japanese offices are equipped with a single large window and two doors, all situated behind the department manager’s workspace. Conversely, American offices leverage natural light with windows on two sides, whereas the doors are placed in each corner of the room. There is also a designated section for photocopiers, storage, and conference rooms in American offices, which are the features absent from the more spacious Japanese offices.

Sample 4:

The floor plans illustrate two distinct office layouts, one typical of Japanese design and the other representative of American style.

Overall, the office layout in Japan tends to be designed to facilitate a hierarchical yet communal working environment, with the provision of only tables and chairs. In contrast, the American office provides individual workspaces and incorporates additional rooms for specific functions.

In a typical Japanese office, the department manager’s desk is located at the head of the office where they can overlook the employees in the room. In front of the department manager’s desk are two section manager desks, one on either side of the room. Likewise, the section managers are able to monitor their subordinates sitting at a block of six desks in front of them.

On the other hand, the department manager’s working space in an average American office is situated in one corner of the room, adjacent to which are two section manager offices. Meanwhile, the staff desks are individually organized in rows in the middle of the office space. Unlike the Japanese office, that of the American includes a printer room, storage space, and two conference rooms on the opposite side of the room. Finally, the latter typically has more windows than the former, with large windows installed on two sides of the room.

Sample 5:

The maps present the differences between typical offices in America and Japan. Overall, Japanese companies prefer an open working space, and it also has a more hierarchical structure with managers presented with clear views of employees, whereas an American office is divided into designated sections and rooms for managers and work-related facilities.

Looking at the entrance and windows, an office in the United States generally has twice as many doors and windows as one in Japan. Specifically, the diagram presents four doors at each corner of the rectangular floor plan and two long sets of windows on either wall of an American office area, whereas a Japanese working space is presented with just two doors and one window installed along a wall at the top.

Regarding the interior layout, there are two rooms for section managers and a larger one for a department manager on the right side of an American office. Desks for employees are arranged in two rows in the center, with a printer room, storage area and two conference rooms located to the left of the office. In comparison, the seating arrangement of a Japanese office reflects a clearer management hierarchy with a wide department manager desk and two smaller section manager desks at the top of the single room. Their subordinates face each other and share large rectangular tables in the lower section of the layout.

Sample 6:

The diagrams vividly juxtapose Japanese and American office designs, illustrating the cultural dichotomy in workplace ethos.

Overall, the Japanese layout, with its open-plan structure, fosters collective engagement and managerial transparency. Conversely, the American design, with its emphasis on individual spaces and defined hierarchy, mirrors a preference for privacy and organizational stratification.

Commencing with the Japanese office, it is characterized by a central, prominent desk for the department manager, positioned to oversee the entire workspace. This pivotal location facilitates an efficient supervisory role. Flanking this central command are desks for the section managers, leading to two parallel rows of employee desks. This arrangement promotes an open and collective working environment where interaction and oversight are seamlessly integrated.

Transitioning to the American office, the layout shifts to a more compartmentalized design, indicative of a preference for privacy and individual workspaces. Here, windows punctuate both sides of the office, bathing the space in natural light. The layout is thoughtfully divided into functional zones, with a printer/copier room and storage space anchoring the left corner. This strategic placement underscores the emphasis on operational efficiency. Furthermore, two conference rooms are tactically located to foster collaborative yet private meetings. The section managers' spaces, situated adjacent to the department manager’s room, suggest a clear hierarchical structure, while the employee desks are arranged in isolated clusters, providing each individual with a defined personal area.

Sample 7:

The provided Layouts offer an insightful comparison between a typical American and a Japanese office, each reflecting distinct cultural nuances in workplace design.

Overall, the layouts reveal that the Japanese preference for open, collaborative spaces, against the American emphasis on individualized, hierarchical work environments, each mirroring their respective cultural work values.

The Japanese office layout, characterized by its open-plan structure, places the department manager's desk centrally, serving as a strategic vantage point for overseeing the workspace. This central positioning not only signifies managerial importance but also facilitates an interactive and collective environment, vital in Japanese work culture. Surrounding this are the section manager's desk and parallel rows of employee desks, arranged to promote accessibility and seamless communication.

In contrast, the American office presents a markedly different approach. The layout, favouring compartmentalization, features individualized spaces, reflecting the American emphasis on personal workspace and privacy. Windows flank the sides of the office, ensuring ample natural light, which is a thoughtful touch to enhance work comfort. The office is thoughtfully segmented into distinct zones: a printer/copier room and storage space are located on one side, optimizing operational efficiency, while conference rooms are situated to facilitate private and collaborative meetings. The department and section managers' spaces are strategically positioned to denote a clear hierarchical system, reinforcing the American workplace ethos of structure and individuality.

Sample 8:

The maps compare the typical workspace of Japanese office workers with that of Americans.

The two models display striking differences, including the organization of tables and chairs, along with the arrangement of windows. Another difference involved is the number of facilities available within the office’s capacity.

As for the distribution of tables and chairs, the Japanese use large collaborative group tables, with a row of chairs for staff along each side. At one end of these tables lies a chair for a section manager, adjacent to an individual table and chair for the department manager. In contrast, American staff is assigned independent L-shaped tables together with chairs, all placed in the middle of the room. The working area for managers, located to the right, is separated from that for staff.

Windows in the Japanese office are concentrated behind the department manager, while those in the American workspace are installed on the sides.

Unlike their Japanese counterparts, American office workers are provided with several facilities, such as a printer and copier, a storage zone, and two conference rooms, right inside the office.

Sample 9:

The comparative images delineate the contrasting layouts of a standard office in Japan and America.

Overall, Japan favors a collective working environment, while America emphasizes an individualistic work style.

In the Japanese office, the arrangement is notably centered around promoting collaboration among team members. Tables are clustered together, organized into two expansive areas, each overseen by a section manager. The department manager’s workstation is strategically positioned to overlook the joint desks of subordinates, granting them a comprehensive view to supervise office activities. Conversely, the American office space is compartmentalized into distinct cubicles, demarcated by tall partitions, aimed at minimizing distractions and fostering individual focus. The managerial team’s workstations, including two section managers and one department manager, are situated separately, partitioned off on the east side.

There is a discernible contrast in the presence of natural light sources. The Japanese office layout is characterized by only one window positioned behind the department manager’s seat. In contrast, the American office features two windows stretching across the western and eastern walls, illuminating the workspace. Additionally, while the American office is equipped with amenities such as a printer, copier, storage facilities, and two conference rooms, the Japanese office lacks these provisions.

Sample 10:

The pictures compare the layout between an ordinary American office and a Japanese one. Overall, the American style is more accessible with extra doors and windows, along with separate amenity rooms. Additionally, Japanese offices feature collaborative workspaces, whereas American ones facilitate individual workstations.

Regarding conventional Japanese offices, windows are positioned between the two entrances situated in the upper extremities of the space. A department manager desk is located in the top midsection with its back against the windows. Below this are two workstations housing section managers facing downwards to a collection of staff tables and chairs that are adjacent to one another.

Concerning regular American offices, four doors are situated in the four corners and windows are placed on both sides. Working areas for employees are spatially separated and arranged in the center of the office, from the top to bottom, each consisting of an L- shaped table and a chair. A printer and copier section, storage, and two conference rooms are constructed separately from the top to the lower left, respectively; meanwhile, two individual section manager rooms and a department manager office are located on the right.

Sample 11:

The visual comparison illustrates two distinct office setups: the traditional Japanese office and the contemporary American office.

Overall, Japanese offices typically embrace an open-plan layout, with no private rooms and a preference for communal workspaces. In contrast, American offices tend to follow a more traditional layout, featuring a higher proportion of private offices and cubicles.

Regarding Japanese offices, private rooms are usually absent, and departments are often grouped together. These offices adhere to a hierarchical structure, positioning the department manager centrally, flanked by two section managers within their respective teams. The workspace consists of expansive communal tables with chairs lined up on each side, promoting direct interaction among employees. Windows are only situated behind the department managers, while the rest of the office lacks windows.

Conversely, American-style offices feature an open space at the center, furnished with L-shaped tables and chairs designated for individual employees. On one side, each manager occupies a private room, with the department manager having the largest one. On the opposite side, there are additional facilities such as a copy room, storage space, and two conference rooms, amenities notably absent in Japanese offices. Windows are installed on both sides of these American offices.

Sample 12:

The given diagrams illustrate the structural differences between a standard office in Japan and the United States.

The office configurations in the two countries are markedly distinct, reflecting divergent approaches to workspace organization. While the Japanese office prioritizes collaborative work, the American office embraces an independent working style.

In Japan, employees are strategically positioned in joint desks, fostering group interactions. The workspaces of the section and department manager, which follow a hierarchy design, are placed to overlook the workstations of subordinates, allowing comprehensive monitoring. Conversely, in America, where the size of one’s workspace corresponds directly to their position. Each staff member is allocated in individual cubicles with high walls and high-ranking executive officers have their own private rooms, both of which ensure privacy.

When it comes to utilization, the team-oriented layout of Japan can accommodate a greater number of workers with its minimalism style compared to American space. However, the U.S setting has more windows and specific function facilities like copier, storage and conference rooms.

Sample 13:

The diagrams depict variances in office layouts between the United States and Japan.

In general, a Japanese office has the characteristic of being an open-plan and hierarchical workspace, allowing managerial oversight of subordinates. In contrast, an American office is divided by partition walls and segmented into various designated cubicles for work-related purposes and rooms for management positions.

Starting with entrances and windows, an American office typically features twice as many doors and windows compared to its Japanese counterparts. Specifically, four entry doors for the American office are positioned at each of the four corners of its rectangular office layout, along with two expansive windows that largely span the western and eastern walls.

On the contrary, a Japanese office consists of only two entrance doors located in the front left and right corners, along with windows that cover one third of the northern wall.

Regarding the interior layout, upon entering the American office through the northeast door, managers have access to two areas designated for section managers and one for a department manager. Desks and chairs are arranged in two rows in the central area of the office. On the left side, there is a room for printers and copiers, as well as a storage area. To the south of these areas, there are two conference rooms.

In contrast, the seating arrangement in a Japanese office clearly reflects the management hierarchy, with a long desk for the department manager positioned just behind the windows. Across the two sections reserved for managers, six workers share a common work table within each section, arranged to face each other and supervised by a section manager.

Sample 14:

The two diagrams illustrate the arrangement in a standard American office compared with that in a Japanese office.

Overall, both offices represent significantly different layouts and functional facilities. The Japanese office prefers a communal working area for supervisors and subordinates, whereas Americans prefer simplicity which provides private space for managers and employees.

The whole sitting area in a Japanese office is shaped like a pyramid, with employees sitting around rectangular tables adjacent to the section managers and department managers. In the American office, however, there are eight semi-closed cubicles in the central area where employees can intermingle. The department and section managers are evenly separated in different cabins.

Another main difference is that there are many specific areas in the American office, such as conference room, storage, and copy. Yet, no such office facilities can be seen in the Japanese office. Besides, the Japanese office enjoys a huge window towards the north behind the department manager, while the windows in the American office are sited on either side, nearly stretching across the whole wall.

Hot: 1000+ Đề thi giữa kì 2 file word cấu trúc mới 2026 Toán, Văn, Anh... lớp 1-12 (chỉ từ 60k). Tải ngay

CÂU HỎI HOT CÙNG CHỦ ĐỀ

Lời giải

Sample 1:

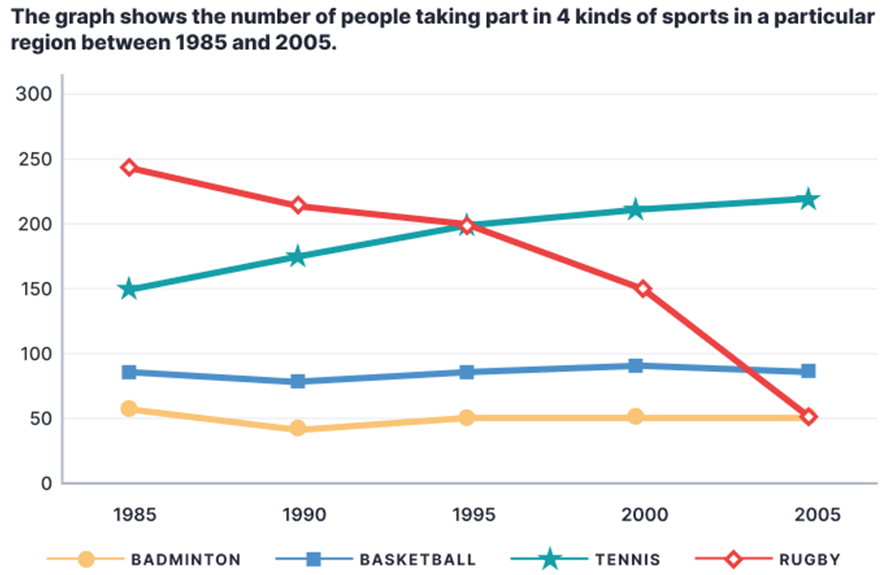

The line chart illustrates how many people participated in 4 distinct types of sports in a particular area from 1985 to 2005.

Overall, rugby was the most popular sport in the first half of the period while tennis took the lead in the second half. In addition, rugby saw a downward trend while tennis took the opposite direction; moreover, the trends for basketball and badminton were relatively stable.

In 1995, the number of people playing rugby stood at just under 250, surpassing the figure for tennis players by around 100. Basketball and badminton had comparatively lower participation rates, with around 80 and 50 participants in turn.

Afterwards, the number of people participating in rugby plunged, hitting a low of 50 in 2005, equal to the figure for badminton in the same year. In contrast, the trend for tennis was upward, with its participation rate increasing to roughly 220 people at the end of the period, establishing it as the leading sport. Finally, the figures for basketball and badminton underwent negligible changes, hovering around 80 and 50 participants respectively.

Sample 2:

The line graph illustrates how many people participated in four types of sports in a specific area from 1985 to 2005. Overall, there was a significant decrease in the number of people playing rugby in this region, whereas tennis showed a gradual upward trend to become the most popular sport in the second half of the period. Additionally, throughout the period, the trends for basketball and badminton were relatively stable and comparable, with the latter sport remaining the least common.

In the first decade, rugby had the highest number of players, despite witnessing a steady fall from nearly 250 to exactly 200 participants. From 1995 onwards, this sport kept losing popularity as its figure plummeted, reaching parity with badminton (at 50 people) in the final year.

In contrast, tennis was gaining popularity and had become the dominant category by the end of the timeframe. Specifically, starting at the second highest (at 150), the number of people engaging in tennis rose continually, overtaking that of rugby in 1995 before ending at approximately 250 players.

Meanwhile, roughly 80 people played basketball initially, after which it stayed virtually unchanged until the end of the period. Badminton almost exactly mirrored this trend, albeit at a lower rate, consistently hovering around the 50 mark.

Sample 3:

The line chart compares the number of participants in basketball, tennis, badminton and rugby over a 20-year period from 1985 in a specific area.

Overall, more people played tennis throughout the period, and it was the most common sport since 1995, while rugby's popularity declined. Notably, basketball and badminton mostly had stable numbers of players.

In terms of tennis and rugby, both sports indicated inverted trends. Although rugby started at the highest point with nearly 250 players, the figure declined continually to about 200 players in 1995, when this sport was no longer the most popular. Since then, the number of people playing rugby dropped more steeply, reaching 50 in 2005. In contrast, from 1985 onwards, the figure for tennis increased steadily from second place with 150 participants. By 2005, it had reached its highest point of roughly 220 players.

In comparison, there were far fewer people who took up basketball and badminton. However, these sports remained relatively stable, with basketball having about 70 participants every year, while badminton was always the least popular with approximately 50 players each year.

Sample 4:

The line graph provides information about the number of individuals engaging in four types of sports in a specific area from 1985 to 2005.

Overall, while tennis underwent a surge in popularity, rugby experienced a decrease in participation within this region over time, with basketball and badminton remaining relatively stable. Moreover, the most drastic shift in popularity was witnessed in rugby.

At the start of the period, in 1985, rugby was the most played sport, with 240 individuals participating, and it significantly outnumbered the next sport, tennis, which had only 150 participants. Thereafter, the number of people playing rugby dropped to 200 in 1995, before plummeting to a 20-year low of 50 in the final year. This stood in stark contrast to the rise in the popularity of tennis, which saw a steady increase in participants to a peak of about 220 in 2005, making it by far the most played sport at the end of the period.

Turning to the remaining sports, in the first year, 80 individuals played basketball, almost 25 more than badminton. Over the following decade, the participant numbers for basketball rose to about 90, while those for badminton dropped to a low of 45 in 1995. In the remaining period, these two sports maintained their popularity, as the numbers participating stayed at roughly the same level until 2005.

Sample 5:

The line chart delineates the participation levels in four distinct sports in a specific area from 1985 to 2005.

Primarily, rugby emerged as the most favored sport in the initial half of the period, while tennis took precedence in the latter half. Moreover, rugby exhibited a declining trend, whereas tennis experienced a converse trajectory. Meanwhile, the engagement rates for basketball and badminton remained relatively consistent.

In 1985, the number of rugby participants stood at just below 250, exceeding the tennis players by approximately 150 individuals. Simultaneously, basketball and badminton showcased lower participation rates, with around 80 and 50 individuals involved in each sport, respectively.

Subsequently, rugby participation plummeted significantly, reaching a nadir of 50 participants in 2005, akin to the number engaged in badminton during the same year. Conversely, tennis experienced an upward trend, escalating to nearly 220 individuals by the conclusion of the period, solidifying its status as the predominant sport. In contrast, the figures for basketball and badminton remained relatively stable, with approximately 80 and 50 participants, respectively, throughout the entire duration.

Sample 6:

The given line graph delineates the participation levels in 4 different sports, namely basketball, tennis, badminton, and rugby within a specific region over a span of 20 years.

Overall, it is evident that the number of individuals participating in tennis witnessed a consistent and notable increase, contrasting sharply with the downward trend observed in rugby participation. Meanwhile, while basketball and badminton recorded lower participation rates compared to other sports, they remained relatively stable throughout the entire period.

Turning to the number of tennis players, the figures began at a relatively moderate level of 150 individuals in 1985. Subsequently, it experienced a gradual and consistent increase in participation, reaching a pinnacle of nearly 230 participants by 2005. In stark contrast, the trend of rugby involvement presented a distinctive pattern. Commencing at a relatively high level of almost 240 people, the numbers steadily declined over time and by the end of the 20-year period, rugby participants had dwindled to 50, matching the level of engagement observed in badminton. Interestingly, a point of convergence occurred in 1995, where both tennis and rugby shared a similar number of participants, with approximately 200 individuals engaging in each sport.

In regard to the remaining sports participants, the numbers for both badminton and basketball remained relatively stable over the given time frame. Beginning with approximately 50 individuals engaging in badminton and around 80 individuals involved in basketball in 1985, these figures persisted with little variation until 2005. Consequently, by the end of the period, both sports witnessed a culmination with nearly the same number of participants as they had at the beginning.

Lời giải

Sample 1:

Many young people work on a voluntary basis, and this can only be beneficial for both the individual and society as a whole. However, I do not agree that we should therefore force all teenagers to do unpaid work.

Most young people are already under enough pressure with their studies, without being given the added responsibility of working in their spare time. School is just as demanding as a full-time job, and teachers expect their students to do homework and exam revision on top of attending lessons every day. When young people do have some free time, we should encourage them to enjoy it with their friends or to spend it doing sports and other leisure activities. They have many years of work ahead of them when they finish their studies.

At the same time, I do not believe that society has anything to gain from obliging young people to do unpaid work. In fact, I would argue that it goes against the values of a free and fair society to force a group of people to do something against their will. Doing this can only lead to resentment amongst young people, who would feel that they were being used, and parents, who would not want to be told how to raise their children. Currently, nobody is forced to volunteer, and this is surely the best system.

In conclusion, teenagers may choose to work for free and help others, but in my opinion, we should not make this compulsory.

Sample 2:

Some individuals nowadays feel that youngsters should accomplish unpaid volunteer work in their leisure time for the benefit of society. I completely believe that it is critical to involve children in volunteer activity. The primary issues will be discussed with examples in this essay.

To begin with, teenagers who participate in unpaid employment are more responsible for local society. When adolescents interact with other individuals, they become aware of the issues that people face daily, such as poverty, pollution, and others. Furthermore, we have all been affected by the present COVID-19 outbreak, and many people have suffered a loss. According to "The Voice of Vietnam - VOV” a volunteer who is anti-virus and empathizes with the mental pain that the patients are experiencing, he always gives oxygen and food to those who need it the most. As a result, volunteering helps students become the most responsible citizens in the country.

Furthermore, unpaid employment can assist youngsters in broadening their social contacts and developing soft skills. Because when they work in an unpaid job, they will meet a variety of individuals and acquire a range of skills and abilities from others, such as leadership, teamwork, communication, and dealing with challenging situations. For example, a recent study in Japan discovered that students who participate in volunteer work are more sociable, enthusiastic, and tolerant of others. They will grow more extroverted, energetic, and hard-working as compared to youngsters who do not perform unpaid employment.

To conclude, I feel that rather than paying, young people should perform unpaid social work because they can acquire many important skills and are more responsible to society.

Sample 3:

There is a growing debate about whether all adolescents should be asked to perform mandatory volunteer work in their leisure time to help assist the surrounding area. Although there are a variety of benefits associated with this topic, there are also some notable drawbacks, as will now be discussed.

The advantages of teenagers doing voluntary work are self-evident. The first relevant idea is work experience. A valid illustration of this would be to increase their tangible skills. For example, an adolescent who volunteers to help in a customer service department will learn how to communicate effectively with people in different age groups. On a psychological level, the youth’s life skills will also be enhanced by having empathy towards others. This can be demonstrated by volunteering and assisting families living in low socio-economic backgrounds with their day-to-day tasks.

There are, however, also drawbacks that need to be considered. On an intellectual level, the teenager may get distracted from their study. This situation, for instance, can be seen when voluntary work is also being undertaken during school terms. There would be time constraints for both areas. On a physiological level, youth might experience fatigue as they are unaware of the acceptable working or volunteering hours and, as a result, sometimes they can be overworked.

In summary, we can see that this is clearly a complex issue as there are significant advantages and disadvantages. I personally believe that it would be better not to encourage the youths to do compulsory work because their studies might take them to a higher level in society, whereas volunteering could restrict this progress.

Sample 4:

Children are the backbone of every country. So, there are people who tend to believe that youngsters should be encouraged to initiate social work as it will result in flourished society and individualistic growth of youngsters themselves. I, too, believe that this motivation has more benefits than its drawbacks.

To begin with, social work by children can be easily associated with personality development because, during this drive, they tend to communicate with the variety of people, which leads to polished verbal skills. For example, if they start convincing rural people to send their children to school, they have to adopt a convincing attitude along with developed verbal skills to deal with the diverse kinds of people they encounter. This improved skill will help them lifelong in every arena. Apart from this, the true values of life like tolerance, patience, team spirit, and cooperation can be learned. Besides that, young minds serve the country with full enthusiasm that gives the feeling of fulfillment and self-satisfaction. This sense of worthiness boosts their self-confidence and patriotic feelings. Moreover, experiencing multiple cultures and traditions broadens their horizons and adds another feather to their cap.

However, it is truly said, no rose without thrones. Can the drawbacks of this initiation be ignored? Children go to school, participate in different curriculum activities, endure the pressure of peers, parents, and teachers and in the competitive world, they should not be expected to serve society without their self-benefits. This kind of pressure might bring resentment in their mind.

In conclusion, I believe, the notion of a teenager doing unpaid work is indeed good but proper monitoring and care should be given to avoid untoward consequences.

Sample 5:

Youngsters are the building blocks of the nation and they play an important role in serving society because at this age they are full of energy not only mentally but physically also. Some people think that the youth should do some voluntary work for society in their free time, and it would be beneficial for both of them. I agree with the statement. It has numerous benefits which will be discussed in the upcoming paragraphs.

To begin with, they could do a lot of activities and make their spare time fruitful. First of all, they can teach children to live in slum areas because they are unable to afford education in schools or colleges. As a result, they will become civilized individuals and do not indulge in antisocial activities. By doing this they could gain a lot of experience and become responsible towards society. It would be beneficial in their future perspective.

In addition to this, they learn a sense of cooperation and sharing with other people of the society. for instance, they could grow plants and trees at public places, and this would be helpful not only to make the surrounding clean and green but reduce the pollution also to great extent. Moreover, they could arrange awareness programmes in society and set an example among the natives of the state. This will make the social bonding strong between the individuals and this will also enhance their social skills.

In conclusion, they can “kill two birds with one stone” because it has a great advantage both for the society and for the adolescents. Both the parents, as well as teachers, should encourage the teens to take part in the activities of serving the community in their free time.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.