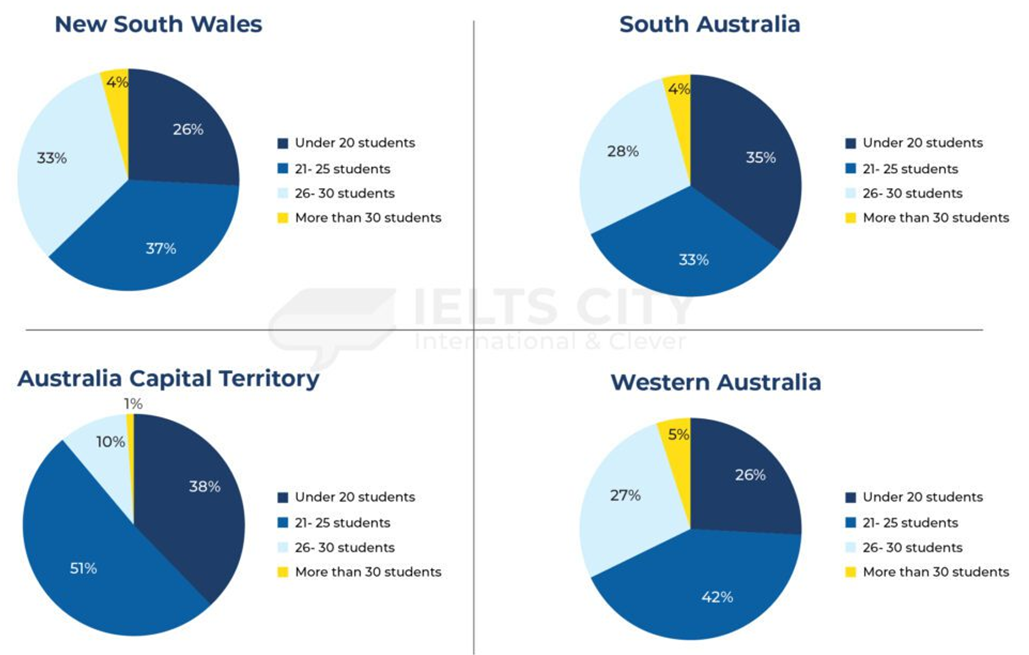

The pie charts show the size of classes in primary schools in four states in Australia in 2010.

Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant. Write at least 150 words.

The pie charts show the size of classes in primary schools in four states in Australia in 2010.

Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant. Write at least 150 words.

Câu hỏi trong đề: 2000 câu trắc nghiệm tổng hợp Tiếng Anh 2025 có đáp án !!

Quảng cáo

Trả lời:

Sample 1:

These four provided pie charts illustrate the distribution of several primary school class sizes across four Australian states in 2010: New South Wales, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, and Western Australia.

Overall, it can be seen that while medium-sized classes are a common feature in these states, the prevalence of smaller and larger classes varies, likely reflecting diverse educational policies or regional challenges.

A common trend is the preference for class sizes of 21-25 students across all states. This range is most prominent in the Australian Capital Territory, representing nearly half the classes (51%), suggesting a regional preference for medium-sized classes. In New South Wales and Western Australia, these classes form nearly two-fifths, with 37% and 42%, respectively.

Classes with 20 students or fewer vary notably among the states, being most common in the Australian Capital Territory (38%) and South Australia (35%), and less so in New South Wales and Western Australia (both 26%). This variation may reflect different educational strategies or demographics.

Larger classes with 26-30 students are somewhat evenly distributed, with New South Wales and South Australia having around a third and a quarter of their classes in this range, respectively. In contrast, the Australian Capital Territory has only 10% of its classes in this size, indicating a distinct approach to class sizes.

Classes exceeding 30 students are rare across the board, ranging from 1% in the Australian Capital Territory to 5% in Western Australia, pointing to a general policy against very large class sizes.

Sample 2:

The presented pie charts offer an elaborate breakdown of class capacities in primary schools in four different areas in Australia in the year 2010.

In an overarching context, it can be explicitly observed that the most notable paradigm was the classes exclusively ranging from 21 to 25 students, except for South Australia. Additionally, the classes surpassing 30 students occupied the most trifling segments among the four analyzed regions.

Looking first at New South Wales, 37% of primary-level classes were made up of from 21 to 25 students, closely followed by classes accommodating between 26 to 30 pupils and restricted to a maximum of 20 students (33% and 26% in that order). A different scenario is demonstrated graphically in South Australia where the allocations of class capacities below 31 pupils were from 28% to 35%, with classes with no more than 20 students being the most substantial ones. Strikingly, both regions jointly represented the most insignificant percentage at 4% for classes above 30 students.

Turning to Australia Capital Territory and Western Australia, the prevalent class size was 21-25 students, accounting for slightly over half and 42%, respectively. In the former, the statistics for the smallest class capacity achieved 38%, which outnumbered the 26-30 class size by 28%. However, the opposite trend was true for the latter where the proportions of classes under 20 and 21-25 students depicted some marked dissimilarities, representing 26% and 27% for each. Concurrently, classes exceeding 30 students amounted to the least significant sector, at 1% and 5%.

Sample 3:

The charts give a breakdown of class sizes in primary schools across four Australian regions in 2010.

Overall, classes having 21-25 students held the largest share in all four states surveyed, except for South Australia, where classes with under 20 students were most common. In contrast, classes containing over 29 students were a rarity in these areas.

Looking first at New South Wales, 37% of the primary-level classes in this state had 21-25 students, followed closely by those with 26-30 and fewer than 20 students (33% and 26% respectively). In South Australia, meanwhile, the percentages of classes comprising under 31 students ranged from 28% to 35%, with classes having a maximum of 20 students being the most popular. Notably, the figures for the biggest class size in both states were the same, each standing at only 4%.

Turning to Australia Capital Territory, classes consisting of 21-25 students constituted the majority, at just over half of all class sizes listed, compared to 38% of classes having no more than 20 students. This was in stark contrast to classes with 26-30 students, making up one-tenth of the total, ten times higher than the smallest class size. In Western Australia, the predominant class size was, again, 21-25 students, occupying 42%, while a negligible difference was observed in the proportions of classes with under 20 and 26-30 students, with figures of 26% and 27%, in that order. In the last position was the largest class size, as its share was only 5%.

Sample 4:

The pie charts compare class size distributions in four Australian states: New South Wales, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, and Western Australia in 2010.

Overall, each state exhibited variations in class size ratios, but classes with over 30 students accounted for the smallest proportion of all classes in each state.

Specifically, class size distributions in New South Wales and South Australia showed several similarities and differences. Both states had 4% of classes with more than 30 students, indicating a small proportion of larger classes. Additionally, each of the three remaining class groups, which are fewer than 20 students, 21-25 students and 26-30 students, represented approximately a third of the total number of classes.

Concerning the Australian Capital Territory, classes with 26-30 students constituted 51%, and a significant share of smaller classes with fewer than 20 students at 38%. In contrast, Western Australia favored classes with 21-25 students at 42% and had a more balanced distribution. Furthermore, the Australian Capital Territory had the lowest percentage of classes with over 30 students (1%), while Western Australia had a slightly higher proportion (5%). These variations highlight different class size preferences, with the Australian Capital Territory emphasizing smaller classes and Western Australia leaning toward mid-sized classes of 21-25 students.

Sample 5:

The charts categorize classes in four Australian states based on the number of students attending.

Overall, classes consisting of over 30 students occupy the most modest proportions, while it is more common for classes in the mentioned states to have between 21 and 25 students than larger or smaller sizes.

The Australian Capital Territory is a representative of the two states with the most common class size (21–25 students), while the other is Western Australia, at figures of 51% and 43%, respectively. Classes with 20 students and below, as well as those with 26–30 students, display minor differences between these two states, at 20–25% for the former and 27–29% for the latter.

However, the majority of classes in New South Wales comprise fewer students, with up to 40% consisting of only 20 students and lower, although those with more students are not uncommon, at around 30% individually. Meanwhile, in South Australia, larger classes (26–30 students) account for up to 44%, compared to 23% of those with 21–25 students.

Finally, one salient feature that all four states share is that only a slight number of classes contain more than 30 students, at only 2–3%.

Sample 6:

The pie charts provide information about the average numbers of students per class in different Australian states.

Overall, in all the examined areas, the majority of classes are comprised of fewer than 30 students each, with the class size of 21 to 25 students being the most common, except in South Australia. Meanwhile, the Australia Capital Territory has the smallest average class size compared to the other regions.

Starting with smaller class sizes, Australia Capital Territory takes the lead for classes with 20 students or fewer, at 38%, followed by South Australia, which is 3% lower. The corresponding percentages for New South Wales and Western Australia are smaller, both at 26%. Classes of 21-25 students constitute more than half (51%) of the total in the Australia Capital Territory, which is nearly 10% higher than in Western Australia, where it stands at 42%. This category makes up around one-third of all classes in the other two regions.

In contrast, the larger class size of 26 to 30 students is less prevalent, with the highest percentage observed in New South Wales at 33%, 5-6% higher than in both South Australia and Western Australia. The Australia Capital Territory only has 10% of its classes in this size bracket, and only 1% of their classes exceed 30 students, while the figures for the remaining three states vary from 4% to 5%.

Hot: 1000+ Đề thi giữa kì 2 file word cấu trúc mới 2026 Toán, Văn, Anh... lớp 1-12 (chỉ từ 60k). Tải ngay

CÂU HỎI HOT CÙNG CHỦ ĐỀ

Lời giải

Sample 1:

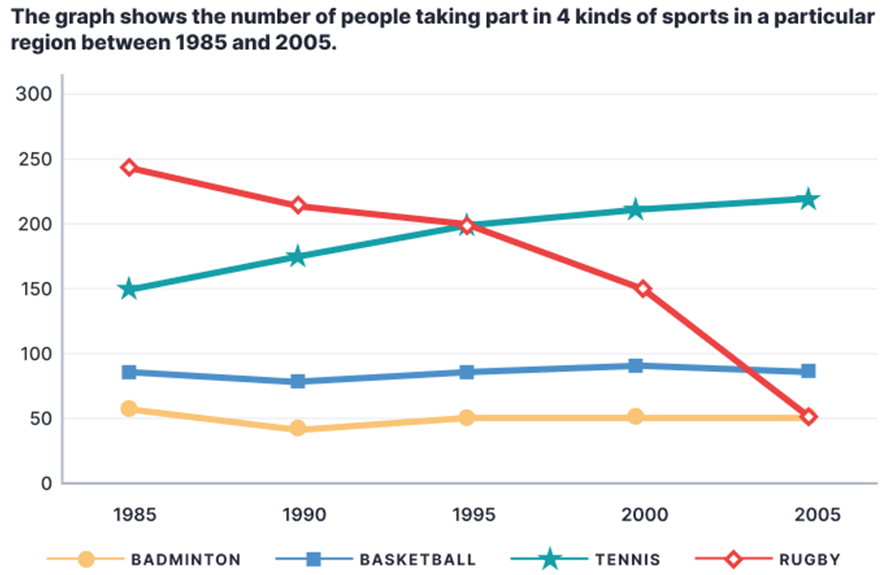

The line chart illustrates how many people participated in 4 distinct types of sports in a particular area from 1985 to 2005.

Overall, rugby was the most popular sport in the first half of the period while tennis took the lead in the second half. In addition, rugby saw a downward trend while tennis took the opposite direction; moreover, the trends for basketball and badminton were relatively stable.

In 1995, the number of people playing rugby stood at just under 250, surpassing the figure for tennis players by around 100. Basketball and badminton had comparatively lower participation rates, with around 80 and 50 participants in turn.

Afterwards, the number of people participating in rugby plunged, hitting a low of 50 in 2005, equal to the figure for badminton in the same year. In contrast, the trend for tennis was upward, with its participation rate increasing to roughly 220 people at the end of the period, establishing it as the leading sport. Finally, the figures for basketball and badminton underwent negligible changes, hovering around 80 and 50 participants respectively.

Sample 2:

The line graph illustrates how many people participated in four types of sports in a specific area from 1985 to 2005. Overall, there was a significant decrease in the number of people playing rugby in this region, whereas tennis showed a gradual upward trend to become the most popular sport in the second half of the period. Additionally, throughout the period, the trends for basketball and badminton were relatively stable and comparable, with the latter sport remaining the least common.

In the first decade, rugby had the highest number of players, despite witnessing a steady fall from nearly 250 to exactly 200 participants. From 1995 onwards, this sport kept losing popularity as its figure plummeted, reaching parity with badminton (at 50 people) in the final year.

In contrast, tennis was gaining popularity and had become the dominant category by the end of the timeframe. Specifically, starting at the second highest (at 150), the number of people engaging in tennis rose continually, overtaking that of rugby in 1995 before ending at approximately 250 players.

Meanwhile, roughly 80 people played basketball initially, after which it stayed virtually unchanged until the end of the period. Badminton almost exactly mirrored this trend, albeit at a lower rate, consistently hovering around the 50 mark.

Sample 3:

The line chart compares the number of participants in basketball, tennis, badminton and rugby over a 20-year period from 1985 in a specific area.

Overall, more people played tennis throughout the period, and it was the most common sport since 1995, while rugby's popularity declined. Notably, basketball and badminton mostly had stable numbers of players.

In terms of tennis and rugby, both sports indicated inverted trends. Although rugby started at the highest point with nearly 250 players, the figure declined continually to about 200 players in 1995, when this sport was no longer the most popular. Since then, the number of people playing rugby dropped more steeply, reaching 50 in 2005. In contrast, from 1985 onwards, the figure for tennis increased steadily from second place with 150 participants. By 2005, it had reached its highest point of roughly 220 players.

In comparison, there were far fewer people who took up basketball and badminton. However, these sports remained relatively stable, with basketball having about 70 participants every year, while badminton was always the least popular with approximately 50 players each year.

Sample 4:

The line graph provides information about the number of individuals engaging in four types of sports in a specific area from 1985 to 2005.

Overall, while tennis underwent a surge in popularity, rugby experienced a decrease in participation within this region over time, with basketball and badminton remaining relatively stable. Moreover, the most drastic shift in popularity was witnessed in rugby.

At the start of the period, in 1985, rugby was the most played sport, with 240 individuals participating, and it significantly outnumbered the next sport, tennis, which had only 150 participants. Thereafter, the number of people playing rugby dropped to 200 in 1995, before plummeting to a 20-year low of 50 in the final year. This stood in stark contrast to the rise in the popularity of tennis, which saw a steady increase in participants to a peak of about 220 in 2005, making it by far the most played sport at the end of the period.

Turning to the remaining sports, in the first year, 80 individuals played basketball, almost 25 more than badminton. Over the following decade, the participant numbers for basketball rose to about 90, while those for badminton dropped to a low of 45 in 1995. In the remaining period, these two sports maintained their popularity, as the numbers participating stayed at roughly the same level until 2005.

Sample 5:

The line chart delineates the participation levels in four distinct sports in a specific area from 1985 to 2005.

Primarily, rugby emerged as the most favored sport in the initial half of the period, while tennis took precedence in the latter half. Moreover, rugby exhibited a declining trend, whereas tennis experienced a converse trajectory. Meanwhile, the engagement rates for basketball and badminton remained relatively consistent.

In 1985, the number of rugby participants stood at just below 250, exceeding the tennis players by approximately 150 individuals. Simultaneously, basketball and badminton showcased lower participation rates, with around 80 and 50 individuals involved in each sport, respectively.

Subsequently, rugby participation plummeted significantly, reaching a nadir of 50 participants in 2005, akin to the number engaged in badminton during the same year. Conversely, tennis experienced an upward trend, escalating to nearly 220 individuals by the conclusion of the period, solidifying its status as the predominant sport. In contrast, the figures for basketball and badminton remained relatively stable, with approximately 80 and 50 participants, respectively, throughout the entire duration.

Sample 6:

The given line graph delineates the participation levels in 4 different sports, namely basketball, tennis, badminton, and rugby within a specific region over a span of 20 years.

Overall, it is evident that the number of individuals participating in tennis witnessed a consistent and notable increase, contrasting sharply with the downward trend observed in rugby participation. Meanwhile, while basketball and badminton recorded lower participation rates compared to other sports, they remained relatively stable throughout the entire period.

Turning to the number of tennis players, the figures began at a relatively moderate level of 150 individuals in 1985. Subsequently, it experienced a gradual and consistent increase in participation, reaching a pinnacle of nearly 230 participants by 2005. In stark contrast, the trend of rugby involvement presented a distinctive pattern. Commencing at a relatively high level of almost 240 people, the numbers steadily declined over time and by the end of the 20-year period, rugby participants had dwindled to 50, matching the level of engagement observed in badminton. Interestingly, a point of convergence occurred in 1995, where both tennis and rugby shared a similar number of participants, with approximately 200 individuals engaging in each sport.

In regard to the remaining sports participants, the numbers for both badminton and basketball remained relatively stable over the given time frame. Beginning with approximately 50 individuals engaging in badminton and around 80 individuals involved in basketball in 1985, these figures persisted with little variation until 2005. Consequently, by the end of the period, both sports witnessed a culmination with nearly the same number of participants as they had at the beginning.

Lời giải

Sample 1:

Many young people work on a voluntary basis, and this can only be beneficial for both the individual and society as a whole. However, I do not agree that we should therefore force all teenagers to do unpaid work.

Most young people are already under enough pressure with their studies, without being given the added responsibility of working in their spare time. School is just as demanding as a full-time job, and teachers expect their students to do homework and exam revision on top of attending lessons every day. When young people do have some free time, we should encourage them to enjoy it with their friends or to spend it doing sports and other leisure activities. They have many years of work ahead of them when they finish their studies.

At the same time, I do not believe that society has anything to gain from obliging young people to do unpaid work. In fact, I would argue that it goes against the values of a free and fair society to force a group of people to do something against their will. Doing this can only lead to resentment amongst young people, who would feel that they were being used, and parents, who would not want to be told how to raise their children. Currently, nobody is forced to volunteer, and this is surely the best system.

In conclusion, teenagers may choose to work for free and help others, but in my opinion, we should not make this compulsory.

Sample 2:

Some individuals nowadays feel that youngsters should accomplish unpaid volunteer work in their leisure time for the benefit of society. I completely believe that it is critical to involve children in volunteer activity. The primary issues will be discussed with examples in this essay.

To begin with, teenagers who participate in unpaid employment are more responsible for local society. When adolescents interact with other individuals, they become aware of the issues that people face daily, such as poverty, pollution, and others. Furthermore, we have all been affected by the present COVID-19 outbreak, and many people have suffered a loss. According to "The Voice of Vietnam - VOV” a volunteer who is anti-virus and empathizes with the mental pain that the patients are experiencing, he always gives oxygen and food to those who need it the most. As a result, volunteering helps students become the most responsible citizens in the country.

Furthermore, unpaid employment can assist youngsters in broadening their social contacts and developing soft skills. Because when they work in an unpaid job, they will meet a variety of individuals and acquire a range of skills and abilities from others, such as leadership, teamwork, communication, and dealing with challenging situations. For example, a recent study in Japan discovered that students who participate in volunteer work are more sociable, enthusiastic, and tolerant of others. They will grow more extroverted, energetic, and hard-working as compared to youngsters who do not perform unpaid employment.

To conclude, I feel that rather than paying, young people should perform unpaid social work because they can acquire many important skills and are more responsible to society.

Sample 3:

There is a growing debate about whether all adolescents should be asked to perform mandatory volunteer work in their leisure time to help assist the surrounding area. Although there are a variety of benefits associated with this topic, there are also some notable drawbacks, as will now be discussed.

The advantages of teenagers doing voluntary work are self-evident. The first relevant idea is work experience. A valid illustration of this would be to increase their tangible skills. For example, an adolescent who volunteers to help in a customer service department will learn how to communicate effectively with people in different age groups. On a psychological level, the youth’s life skills will also be enhanced by having empathy towards others. This can be demonstrated by volunteering and assisting families living in low socio-economic backgrounds with their day-to-day tasks.

There are, however, also drawbacks that need to be considered. On an intellectual level, the teenager may get distracted from their study. This situation, for instance, can be seen when voluntary work is also being undertaken during school terms. There would be time constraints for both areas. On a physiological level, youth might experience fatigue as they are unaware of the acceptable working or volunteering hours and, as a result, sometimes they can be overworked.

In summary, we can see that this is clearly a complex issue as there are significant advantages and disadvantages. I personally believe that it would be better not to encourage the youths to do compulsory work because their studies might take them to a higher level in society, whereas volunteering could restrict this progress.

Sample 4:

Children are the backbone of every country. So, there are people who tend to believe that youngsters should be encouraged to initiate social work as it will result in flourished society and individualistic growth of youngsters themselves. I, too, believe that this motivation has more benefits than its drawbacks.

To begin with, social work by children can be easily associated with personality development because, during this drive, they tend to communicate with the variety of people, which leads to polished verbal skills. For example, if they start convincing rural people to send their children to school, they have to adopt a convincing attitude along with developed verbal skills to deal with the diverse kinds of people they encounter. This improved skill will help them lifelong in every arena. Apart from this, the true values of life like tolerance, patience, team spirit, and cooperation can be learned. Besides that, young minds serve the country with full enthusiasm that gives the feeling of fulfillment and self-satisfaction. This sense of worthiness boosts their self-confidence and patriotic feelings. Moreover, experiencing multiple cultures and traditions broadens their horizons and adds another feather to their cap.

However, it is truly said, no rose without thrones. Can the drawbacks of this initiation be ignored? Children go to school, participate in different curriculum activities, endure the pressure of peers, parents, and teachers and in the competitive world, they should not be expected to serve society without their self-benefits. This kind of pressure might bring resentment in their mind.

In conclusion, I believe, the notion of a teenager doing unpaid work is indeed good but proper monitoring and care should be given to avoid untoward consequences.

Sample 5:

Youngsters are the building blocks of the nation and they play an important role in serving society because at this age they are full of energy not only mentally but physically also. Some people think that the youth should do some voluntary work for society in their free time, and it would be beneficial for both of them. I agree with the statement. It has numerous benefits which will be discussed in the upcoming paragraphs.

To begin with, they could do a lot of activities and make their spare time fruitful. First of all, they can teach children to live in slum areas because they are unable to afford education in schools or colleges. As a result, they will become civilized individuals and do not indulge in antisocial activities. By doing this they could gain a lot of experience and become responsible towards society. It would be beneficial in their future perspective.

In addition to this, they learn a sense of cooperation and sharing with other people of the society. for instance, they could grow plants and trees at public places, and this would be helpful not only to make the surrounding clean and green but reduce the pollution also to great extent. Moreover, they could arrange awareness programmes in society and set an example among the natives of the state. This will make the social bonding strong between the individuals and this will also enhance their social skills.

In conclusion, they can “kill two birds with one stone” because it has a great advantage both for the society and for the adolescents. Both the parents, as well as teachers, should encourage the teens to take part in the activities of serving the community in their free time.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.

Lời giải

Bạn cần đăng ký gói VIP ( giá chỉ từ 199K ) để làm bài, xem đáp án và lời giải chi tiết không giới hạn.